China’s dealmaking heralds the post-America Middle East.

Welcome to the post-America moment in the Middle East.

US influence has been eroding for decades, from the destructive overreach of the post-9/11 years to the transactional diplomacy of President Donald Trump.

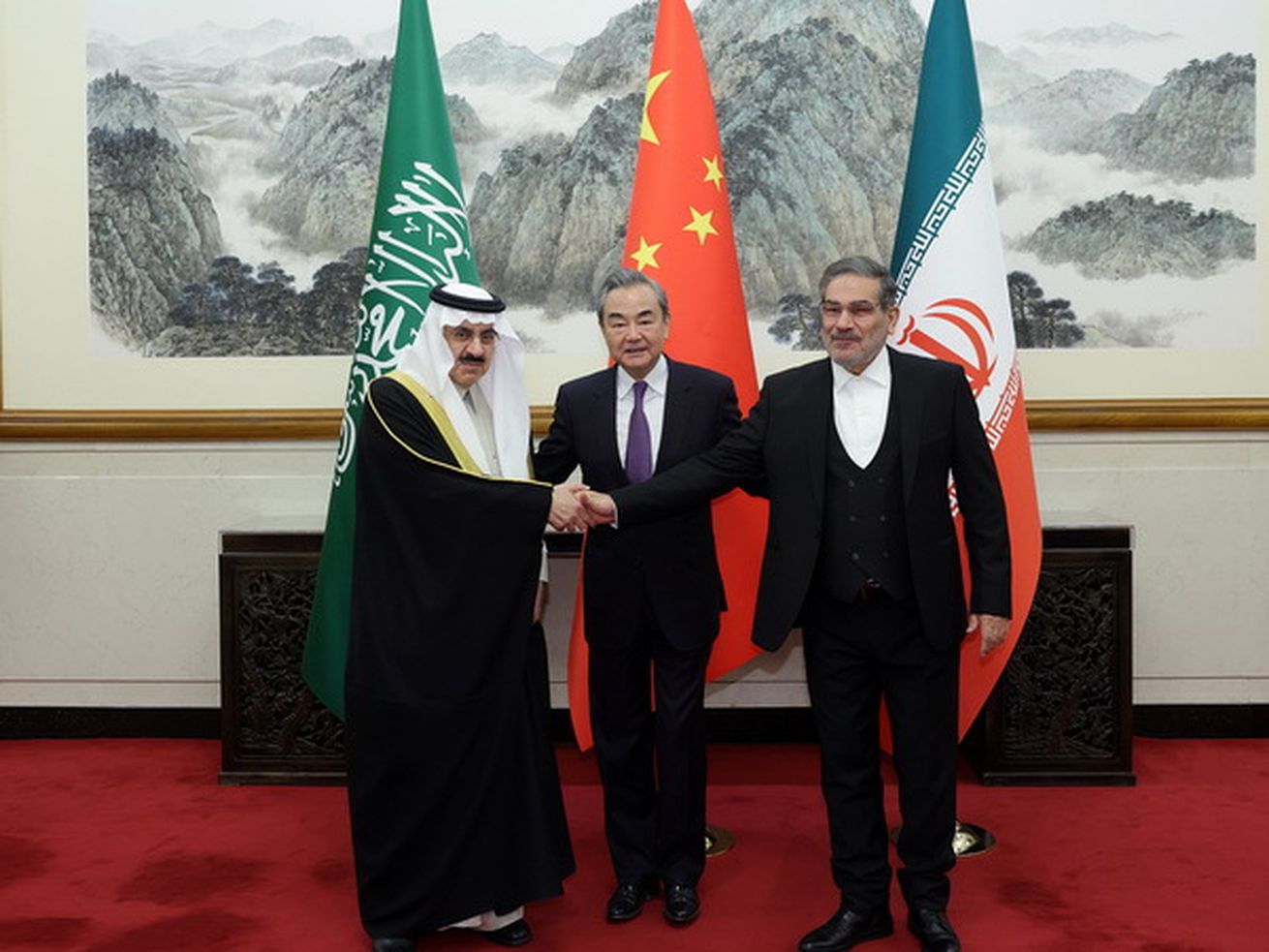

Here we are now officially, with China brokering a detente deal between the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Iran.

On Friday, Saudi Arabia and Iran restarted diplomatic relations after seven years of high tensions and violent exchanges between them. Within two months, they will reopen embassies and have both pledged “respect for the sovereignty of states and noninterference in their internal affairs.” The two countries have been engaged in a proxy war in Yemen over the past eight years that has calmed down until recently, and have been on opposite sides of conflicts throughout the Middle East, in Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq. While normalization may not mean a cessation of violence throughout the region, the pause in outright hostilities between the two should be welcomed by all. The breakthrough builds on several years of talks in Iraq and Oman.

And the most interesting dynamic may be that China led the way.

“If you create a diplomatic vacuum, someone’s going to fill it. That’s basically what’s happened to US policy in the Gulf,” says Chas Freeman, a retired career diplomat with extensive experience in the Middle East and China. “It’s a really major development.”

That China played a role shows where global power is shifting — and a meaningful change in how Chinese President Xi Jinping conducts Middle East policy. Thus far, Beijing has been cautious in taking an active role there; this diplomacy, while significant, doesn’t mean China is trying to displace the US security role in the Middle East, Freeman explained. Instead, China is “trying to produce a peaceful, international environment there, in which you can do business,” he told me.

Saudi Arabia, long a US partner, appears to be shaking off its commitment to a unipolar US world. It says a lot about how Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman conducts foreign policy as the kingdom brings China and Iran closer, in pursuit of security outside traditional Western allies. “MBS has a preference for an alternative world order that is dominated by the likes of Xi and [Russian President Vladimir] Putin,” says Khalid Al-Jabri, a Saudi entrepreneur and physician. “Take away the grievances between the Saudi and the Iranian regimes, and they are actually more alike than they’re different.”

Did US abdication in the Middle East lead to Chinese diplomatic power?

All diplomacy and normalization is good if it leads to more communication and can calm tensions.

Iran and Saudi Arabia are in opposition across the Middle East, in the tragic proxy war in Yemen, where more than 150,000 people have died, as well as in Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq. The rhetoric has been fiery, with MBS comparing the Iranian leader to Hitler. Since then Iran’s pursuit of nuclear enrichment has led Saudi Arabia to seek a civilian nuclear program. Saudi Arabia has often been on alert for Iranian attacks, and it has led to fears of unintended escalation between the two countries that could set off a broader war.

Saudi Arabia had updated the US on the talks, but Washington was not directly involved. The US does not have diplomatic relations with Iran, and Saudi-Iranian rapprochement was not apparently something the Biden administration was working toward.

Freeman, who served as ambassador to Saudi Arabia from 1989 to 1992, has argued that the Saudi Arabia and Gulf monarchies were already forging a foreign policy independent of the US, in response to what they saw as the abdication of the US military responsibility for the Gulf and diplomatic ineptitude.

After Iran interfered in the key energy shipping pathway around and in the Strait of Hormuz and it or its proxy forces attacked a Saudi Aramco facility in Abqaiq in 2019, the US did not respond with military force. Such US restraint may have been smart in terms of not escalating tensions, but it did leave Saudi Arabia and its partners without a sense of US security backing. “Basically, the US defaulted on a long-standing commitment we had to be the strategic backer and defender of the Gulf Arabs,” Freeman told me.

“The context is one in which a diplomatic default by the US has opened an opportunity for someone else to emerge as a peacemaker,” he says. “The region now speaks for itself. It doesn’t follow anybody’s diktats.”

Iran, hampered by ongoing protests against its government, was perhaps more willing to make a deal. And it’s not yet clear whether the normalization of relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia is a true reconciliation or just a brief cessation of hostilities. Regardless, it’s a promising sign for stability in the region for the short term — less so for US influence in it.

It’s a big blow to the Biden administration’s Middle East policy. After pledging to hold Saudi Arabia to account on the presidential trail, Biden visited the kingdom in an about-face last summer in response to high oil prices caused by Russia’s war — and the US didn’t get very much in return. “They are still pursuing an outdated and disproven cold war mentality by doubling down on their existing allies like Saudi Arabia and abandoning all campaign promises, especially on human rights,” Al-Jabri told me.

Both the Biden and Trump administrations tethered their Saudi and Middle East policy to uniting Israel and Gulf states over countering Iran. Iran and Saudi Arabia’s cooling of tensions shows that for all of the kingdom’s harsh anti-Iranian rhetoric in recent years, there is space for collaboration, albeit without a strong US role.

China is the largest trading partner of the Gulf and most of the Middle East, and it has a real stake in an easing of tensions. Looking ahead, Saudi Arabia made a strategic choice here and elsewhere — it’s looking to join the BRICS grouping of developing countries and take on observer status at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

“It indicates that the kingdom wants to focus on domestic economic development over geopolitical conflicts at present, particularly as conflicts in Syria and Yemen settle into stalemate and Iran’s leaders are preoccupied by domestic unrest,” says Andrew Leber, a political scientist focused on Saudi Arabia at Tulane University.

The Iran-Saudi announcement comes as both the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times ran stories teasing the potential of Saudi Arabia and Israel establishing diplomatic ties as part of an expansion of former President Donald Trump’s normalization deals between Israel and Arab states. But analysts I spoke with see little prospect of Israel and Saudi Arabia’s deal of the century. Biden and the US would never agree to Saudi conditions of nuclear power and security guarantees, and Saudi Arabia is unlikely to agree to a real peace deal with Israel.

As for the erosion of US power, the Biden administration politely disagrees. “I would stridently push back on this idea that we’re stepping back in the Middle East — far from it,” White House spokesperson John Kirby said.

Yet for now, there are limits to Biden’s fist-bump diplomacy. The new agreement with some potential to calm the Middle East started not in Washington, but in Beijing.